sermon notes from the Vineyard Church of Milan 08/18/2013

video available at www.sundaystreams.com/go/MilanVineyard/ondemand

podcast here: http://feeds.feedburner.com/VineyardChurchOfMilan

or via iTunes here: https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/vineyard-church-of-milan/id562567379

2nd week in a series entitled “Outsiders.” Having to do with the tension we feel about embracing outsiders, personally, and in the groups we are part of, especially the church. On the one hand, we are drawn to embrace outsiders because of potential benefits they might bring, or out of compassion, or even by curiosity. On the other hand, we are nervous about outsiders because they can bring influences, ideas, practices, etc. that threaten our integrity or mission or uniqueness. We are calling this Love’s tension, because it’s the tension at the heart of love. This topic has application from dating to having children to organizational management to commerce to culture to immigration to social reform.

[Bachelorette example…Brooks dumping Desiree…had to maintain his integrity (purity), but felt like a violation of justice (the pain it caused Des)…yet to not cause the pain would also be an injustice (it would lead her on under false pretenses), and compromise his integrity as well…even though his choice was clear, the tension was powerfully felt]

We are looking at Love’s tension primarily through the lens of how it impacts faith communities, because this is the context in which our book, the Bible, shares its wisdom and witness most directly.

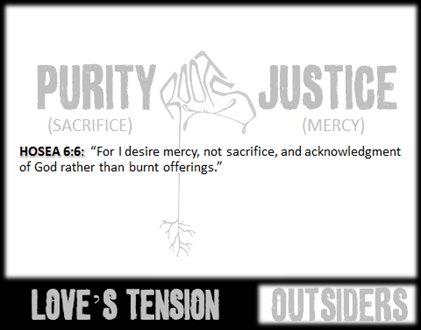

Last week, we looked at the old Testament, the part of the Bible that has to do with Abraham and his descendants, the people of Israel, and their relationship with YHWH, the one true God who authored the universe and is engaged in a cooperative, long term mission with humanity to set right all that has gone wrong in his original creation. We talked about how the Old Testament illustrates love’s tension, the tension between the twin impulses of purity and justice. Purity as illustrated by Israel’s impulse to be true to their calling to be God’s chosen people, faithful to him and his commandments. And justice as illustrated by God’s commands to Israel to treat outsiders in her midst with dignity and fairness, and the prophets’ vision of a future in which today’s outsiders were tomorrow’s full participants in the life of the family of God.

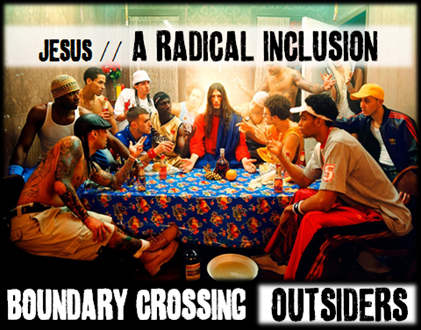

Looking today at the New Testament, and the radical way Jesus related to those whom the insiders in his day and age (the well off, the religious orthodoxy, the powerful, the social watchdogs) considered outsiders. Social outcasts. Tax collectors. Shepherds. Gentiles. Samaritans. The poor. Women. Lepers. The demon possessed. Even those we might call sinners (like the woman caught in adultery, like Zacchaeus, the original white collar criminal).

Jesus approach was unprecedented. On two fronts.

One, Jesus didn't keep outsiders at arm’s length; instead he crossed all kinds of social boundaries and ate with these outsiders, which was a really big deal in his culture. To eat with someone was to treat someone like family, in a day and age in which family bonds were even stronger than they are today. You'd die for family, without hesitation.

And not only did Jesus reach out to these outsiders, but he made them the true insiders in his movement. He invited them to the head of the table by redefining what an insider looked like in the community defined by him.

To Jesus, insiders were anyone willing to be what Philly Vineyard pastor Brad Zinn calls "Arounders." People who were willing to be around Jesus. To stick close by. To listen. To follow where he led. In fact, Jesus taught in parables, he said, in order to be a little bit confusing. So you had to stick around and ask him questions, to wrestle with his meaning. So that those who stayed around and stuck close would get the “secret of the kingdom.” So that people who didn’t stick around wouldn’t understand him, wouldn’t get it. As a result, many who were previously insiders became outsiders – like the Pharisees – and many who were previously outsiders became insiders - like Mary from Magdala, who been afflicted with demons before meeting Jesus, or like the Samaritan woman at the well who’d had more husbands than you could count on one hand.

Jesus, in other words, had a groundbreaking approach to Love’s tension, the tension between purity and justice, the tension between sacrifice and mercy. Jesus’ practice - Radical Inclusion – has something to say to all of us, in every area of our lives where we experience it, and especially in our communities that bear his name.

However, to more deeply understand Radical Inclusion’s relationship to Love’s tension, we need to understand the roots of this tension.

Logically speaking, it’s not a true tension. In other words, logically, we can understand the need to preserve the integrity of a person, or a community of persons organized around a mission or purpose, a set of values and distinctives. This is the purity impulse. And we can understand logically and intellectually the need to pursue justice, for things to line up with the goodness of God. This is the justice impulse. Purity and justice can coexist logically.

For example, revisiting last week’s discussion, we understand, logically and intellectually, why God would want outsiders to be treated with dignity and value as human beings, especially by a people who were once themselves outsiders who had been humiliated and devalued in Egypt. At the same time, we understand, logically and intellectually, why God would not want his family to covenant with anyone outside of the covenant he established with them, because it could cause Israel to lose her integrity as his family. And indeed, that’s what happened when Israel lost her concern for her faithfulness to God. (Background behind the Phineas story…the Midianites deliberate seduction of Israelite men for the purposes of defeating them militarily by getting them to lose the protection of YHWH). There is no logical tension here.

And yet.

Yet.

There is a profound psychological tension that always arises between these two impulses. It’s a tension we feel. Consider Israel’s response when they realized how they had abandoned God after succumbing to the seduction of the Midianites. They expelled the Midianite wives and children from among them, sending them alone and defenseless out into the wilderness, certainly resulting in much suffering and even death. This feels like the right thing to do from the perspective of purity – the contamination must be eliminated so that integrity can be restored. Yet, this also feels like the wrong thing to do from the perspective of justice – others are suffering for the sake of Israel’s healing. And it’s inherently messy – some of us will feel the former emotion more strongly, and others will feel the latter.

The best way to understand this is with Dixie cups.

[Have everyone swallow. Give everyone a Dixie cup. Have them spit in the cup. Ask them to drink their spit.]

What you probably experienced is called core disgust. It’s an emotional, psychological phenomenon. Disgust is a boundary emotion. When our saliva is inside of us, it’s part of us. There is no disgust. As soon as it crosses the boundary of our self, it’s an outsider and somehow unclean.

Logically, swallowing that spit is no different than what you did when you swallowed before you had the Dixie cup. Nothing materially has changed in the physical properties of your saliva. Except that it crossed the boundary between being an insider and an outsider. To not drink perfectly good spit is an injustice of sorts, logically.

And yet most of us still feel disgust at the prospect of drinking it.

Because, psychologically, everything has changed when our spit is an outsider to our bodies. It’s been contaminated somehow and is now a potential contaminant. We feel it.

Disgust is such a powerful emotion because it’s meant to protect us from potentially lethal toxins. In fact, when we feel disgust, our instinct is to spit, or vomit, to retreat, to push away, to expel, to kill (think: insects…).

Anytime we are faced with the purity impulse, disgust is the emotion that comes along for the ride. And anytime you feel disgust, at some level it’s purity of some variety that’s being threatened. And anytime we are dealing with disgust and purity, we are dealing with issues related to boundaries. To the line between what’s inside and what’s outside. To the line between insiders and outsiders. The Dixie cup phenomenon is everywhere.

This is at the heart of Israel’s day of atonement practice, the ritual of symbolically placing the sins of the nation on the back of goat (the scapegoat), and sending it outside the walls of the city into the desert. The high priest would lay his hands on the goat, confess the sins of Israel, while people prostrated themselves and privately confess. Then the goat was led to a cliff outside Jerusalem and pushed off its edge, so that it wouldn’t ever return to the city. It’s an expulsion of the sin toxin from the people, restoring their purity.

One of the problems, though, is that disgust is capable of being misplaced. (Have you seen a twelve year old trying to eat vegetables?) It’s such a powerful emotion, and it’s role is so important, that it will always err in the direction of protection. I know my disgust about the saliva is misplaced, logically. But I still feel it; I don’t want to drink the spit. I know my disgust is misplaced about mushrooms. But I still don’t eat them. I know the snake or the spider won’t hurt me. But I want to get the snake as far away from me as possible. I’d prefer if someone would squish the spider, eliminate it as a potential threat. Even fake snakes, spiders, poop, throw up etc. will all produce the same disgust response in us; this is just how it works. Better safe than sorry, right? Right. Except when we retreat so far into safety that we keep ourselves from God himself. Or when we do injustice to others in the name of God, unwittingly giving God a bad name while trying to preserve our purity in a misguided way so that we can give him a good name.

And it seems as if this error-prone nature of disgust caused these kinds of issues for Israel. The priestly tradition of holiness, sacrifice, and purity came under critique by prophets like Amos and Hosea.

Amos writes this, quoting God:

"I hate, I despise your religious festivals; I cannot stand your assemblies. Even though you bring me burnt offerings and grain offerings, I will not accept them. Though you bring choice fellowship offerings, I will have no regard for them. Away with the noise of your songs! I will not listen to the music of your harps. But let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream!

Amos 5:21-24

And Hosea writes this:

For I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings.

Hosea 6:6

The New Testament makes clear that some kind of disgust / purity / holiness error had happened in Israel at the time of Jesus. The insiders in Israel were concerned about the fact that Israel was under the rule of Rome. It felt like Israel had been unfaithful to God, and were now out of his favor. They needed a return to purity in order to gain his favor again. Who were the contaminants, the toxins that needed to be avoided, neutralized, or perhaps even spit out? Well, they were the sinners, the social outcasts. Tax collectors had gotten in bed with Rome, they were impure. Prostitutes were violating marriage beds and were impure in a different way. Lepers were contagious, and probably were sick because of some other sin of their own, or perhaps their parents, and so they were relegated to leper colonies. Gentiles, and those who rubbed shoulders with them were impure by association. Same with Samaritans. The poor. Sinners. These impurities were Israel’s problem.

The Pharisees made it their mission to do something about Israel’s purity problem. Their solution was to separate the outcasts from the true Israelites, and keep Israel from being contaminated by them by marginalizing them more and more. By keeping them in the Dixie cup. And maybe throwing the Dixie cup away.

But Jesus’ didn’t see things the same way. He didn’t seem disgusted by sinners. He was called a friend of sinners. He invited them to be his followers. He seemed to be under the impression that instead of contaminating his purity, they would in fact be contaminated by his purity. So when he touched a leper, instead of Jesus getting leprosy, the leper was healed. When Zacchaeus, a tax collector who’d cheated his fellow Jews for financial gain and to gain the favor of Israel’s enemy, Rome, climbs a tree to see Jesus, Jesus invites himself over for dinner, and Zacchaeus ends up giving half his wealth to the poor, and paying back anyone he’d cheated 4 times more than he’d taken. Jesus has no fear of contagions; contagions have fear of him (this is why the demons are always stirring up a ruckus when he is nearby). He’s taking the impure outsiders, treating them as insiders, and in the process, restoring their integrity as human beings.

In fact, what Jesus seems to be arguing through his symbolic actions and words is that it’s not the outsiders that are making Israel impure and must be separated by social boundaries, it’s the boundaries themselves, and those who are maintaining them that are compromising Israel’s integrity.

Listen to Miroslav Volf, from his book Exclusion and Embrace:

An advantage of conceiving of sin as the practice of exclusion is that it names as sin what often passes as virtue…In the Palestine of Jesus’ day…a righteous person had to separate herself from [“sinners”]; their presence defiled because they were defiled. Jesus’ table fellowship with “tax collectors” and sinners,” a fellowship that indisputably belonged to the central features of his ministry, offset this conception of sin. Since he who was innocent, sinless, and fully within God’s camp transgressed social boundaries that excluded outcasts, these boundaries themselves were evil, sinful, and outside God’s will. By embracing the “outcast,” Jesus understood the “sinfulness” of the person and systems that cast them out.

In Matthew 8 and 9, Jesus heals a man with leprosy, heals a Roman centurion’s servant, casts demons out of two violent, demon possessed men, forgives and heals a paralyzed man, and then invites a tax collector to be his disciple. While he’s eating dinner with Matthew’s tax collector and sinner friends, the Pharisees show up and demand an explanation.

Listen to Jesus’ response:

On hearing this, Jesus said, “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. But go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ For I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.”

When Jesus says “I desire mercy, not sacrifice,” he’s quoting the prophet Hosea. I believe he’s saying to the Pharisees that we can’t resolve the tension between justice and purity, between mercy and sacrifice until our hearts, our desire, is love for the outsider that over-rides our misplaced disgust responses and leads to mercy towards them. Only then can we have eyes to see the way God wants us to approach questions of purity.

After all, what is love if it’s not the willingness to relax or suspend disgust so that an outsider can be embraced? Isn’t this what we do when we change our child’s diaper, or wipe snot from her nose? Isn’t this what we do when we kiss? Isn’t this what we do when we care for the sick?

We don’t eat our kids poop, and we still try to keep it off of our bodies as much as possible. But when push comes to shove, we’ll choose mercy over sacrifice, every time, for the sake of love.

This is what Jesus does. He suspends disgust in order to embrace us, all the way to the cross. It’s as if his justice is, in fact, the defining feature of his purity. His mercy is his sacrifice. He loves us. All of us who have been outsiders to God.

Practical Suggestion:

Sit with this parable. [Read “Salvation for a Demon” by Peter Rollins…] Spend some time thinking about it. Talking about it with friends or family. On Friday, pray about it. Ask God if there is anything he wants to show you or say to you through your engagement with this story. Then just wait and listen for one minute. As always, I’d love to know what you hear, so let me know if you’re up for it and it’s not too personal.

No comments:

Post a Comment